In researching Penn Station’s Rise, Fall & Proposed Reincarnation I started with Wikipedia and moved on to other sources. Primary amongst these were; Ada Louise Huxtable the Pulitzer Prize winning architecture critic for the New York Times, Eric Plosky’s comprehensive thesis, The Fall and Rise of Pennsylvania Station submitted to the Department of Urban Studies & Planning at MIT, and the PBS Documentary The Rise and Fall of Penn Station. Links to these are at the bottom.

The Rise, Fall, & Proposed Reincarnation of Penn Station

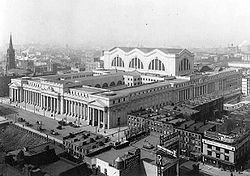

In 1910, the Pennsylvania Railroad successfully accomplished the enormous engineering feat of building tunnels under New York City’s Hudson and East Rivers, connecting the railroad to New York and New England, knitting together the entire eastern half of the United States. The tunnels terminated in what was one of the greatest architectural achievements of its time, Pennsylvania Station. Penn Station covered nearly eight acres, extended two city blocks, and housed one of the largest public spaces in the world. But just 53 years after the station’s opening, the monumental building that was supposed to last forever, to herald and represent the American Empire, was slated to be destroyed.

The controversy over the demolition of such a well-known landmark, and its deplored replacement, is often cited as a catalyst for the architectural preservation movement in the United States. New laws were passed to restrict such demolition. Within the decade, Grand Central Terminal was protected under the city’s new landmarks preservation act, a protection upheld by the courts in 1978 after a challenge by Grand Central’s owner, Penn Central.

Penn Station was really the great martyr of historic preservation, the building that died so that we might save others in the future. What Penn Station was, was the tipping point. Something that people simply wouldn’t accept any more. And so then there was the political will to do something about it. Paul Goldberger, Architecture Critic – PBS Documentary – The Rise and Fall of Penn Station.

Penn Station (Pennsylvania Station) New York City

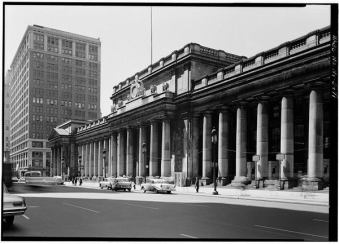

Penn Station Waiting Room (L), and Front Entrance (R).

Pennsylvania Station, also known as New York Penn Station or Penn Station, is the main intercity train station in New York City. Serving over 600,000 commuter rail and Amtrak passengers a day at a rate of up to one thousand passengers every 90 seconds, it is the busiest passenger transportation facility in the United States and in North America.The station is located in Midtown Manhattan close to the Empire State Building, and the Macy’s Department Store. The station is underground beneath Madison Square Garden. The original Pennsylvania Station was inspired by the Gare d’Orsay in Paris (the world’s first electrified rail terminal) and was constructed by the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1901 to 1910. After a decline in passenger usage during the 1950s the original station was demolished in 1963 and replaced in 1969 with the current station. Future plans for Pennsylvania Station include the possibility of relocating some trains into the adjacent Farley Post Office, a building designed by the same architects as the original 1910 Pennsylvania Station structure.

History

Planning and Construction (1901–1910)

Beginning in June 1903 the North River Tunnels, two single-track tunnels, were bored from the west under the Hudson River and four single-track tunnels were bored from the east under the East River. Electrification was initially 600 volts DC–third rail. Construction was completed on the Hudson River tunnels on October 9, 1906, and on the East River tunnels March 18, 1908. Meanwhile, ground was broken for Pennsylvania Station on May 1, 1904. By the time of its completion and the inauguration of regular through train service on Sunday, November 27, 1910, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (approximately $2.7 billion in 2011 dollars), according to an Interstate Commission Report.

“The vaulted steel and glass sheds that covered the train platforms lent drama and mystique to the routine act of arriving in a city by train. The stately, soaring interior of the McKim, Mead, and White terminal was an ode to civic architecture, conferring a kind of kingliness on the weary traveler and the workaday commuter. It ennobles the act of daily life,” critic Paul Goldberger notes in one his frequent appearances in the PBS documentary: “The Rise and Fall of Penn Station.”

But if the terminal building was the soul of the project, its heart was an ambitious, massive infrastructure engineering effort that survives to this day—depositing millions of New York–bound travelers into a dingy, comparatively cramped underground warren of tunnels that retains its old name despite its loss of grandeur.

Original Structure (1910–1963)

Penn Station, 1911

Penn Station, Interior, 1935-1938

During half a century of operation under the Pennsylvania Railroad (1910–1963) scores of intercity passenger trains arrived and departed daily to Chicago and St. Louis on “Pennsy” rails and beyond on connecting railroads to Miami and the west. A side effect of the tunneling project was to open the city up to the suburbs, and within 10 years of opening, two-thirds of the daily passengers coming through Penn Station were commuters. By 1945, at its peak, more than 100 million passengers a year traveled through Penn Station. The station saw its heaviest use during World War II, but by the late 1950s intercity, rail passenger volumes had declined dramatically with the coming of the Jet Age and the Interstate Highway System and the railroad was suffering huge financial losses from 1946 into the 50’s.

Beginning of the End

The Pennsylvania Railroad optioned the air rights of Penn Station in the late 1950s. The option called for the demolition of the head house and train shed, to be replaced by an office complex and a new sports complex. The tracks of the station, perhaps fifty feet below street level, would remain untouched. Plans for the new Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden were announced in 1962.

“By 1960, in the eyes of Graham-Paige, it was time to replace the 1925 Madison Square Garden with a modern, more flexible facility that could handle greater crowds, provide more unobstructed views, and usher in a glitzy new look to attract new audiences…There was no public indication at this time that Graham-Paige had entered into negotiations with the Pennsy for the rights to develop on the site of Penn Station. …Graham-Paige will control 75 percent of the stock of the new company and the Pennsylvania Railroad 25 percent. By selling its air rights to the Madison Square Garden Corporation and replacing Penn Station with a more compact underground facility, the Pennsy would “collect $2.1 million per annum in rent, plus some $600,000 in yearly savings on maintenance and operating costs of the terminal.” …The replacement of Penn Station by Madison Square Garden was an ideal business solution for both the Pennsylvania Railroad and Graham-Paige. …The railroad, by replacing Penn Station with an underground facility and selling its air rights, achieved both of its objectives — it significantly cut its overhead and fashioned a modern new image for itself. Graham-Paige, for its part, obtained the largest single building area in Manhattan.” Plosky pp. 22-29

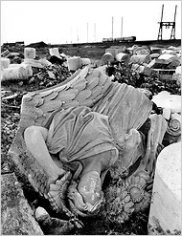

Demolition of the Original Structure

The cost of maintaining the old structure had become prohibitive, so it was considered easier to demolish the old Pennsylvania Station by 1963 and replace it with Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden. Modern architects rushed to save the ornate building, although it was contrary to their own styles. They called the station a treasure and chanted “Don’t Amputate – Renovate” at rallies.Demolition of the above-ground station house began in October 1963.

“Does it make any sense to attempt to preserve a building merely as a “monument” when it no longer serves the utilitarian needs for which it was erected? It was built by private enterprise, by the way, and not primarily as a monument at all but as a railroad station.” A. J. Greenough, President of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, Letter to the New York Times, August 23, 1962

Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic for the NY Times, who would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1970, expressed her outrage at the proposed demolition of Penn Station. She lashed out at the City Planning Commission in her article: “Architecture: How To Kill a City.” New York Times, May 5, 1963.

“What few realized, and this made all of the impassioned pleas for the cultural and architectural values of the city fruitless, was that however much the commission might be moved in the area of its civic conscience by such arguments, it was totally without power to act on them… The decision [to approve construction on Madison Square Garden] rested entirely on whether congestion would be increased by issuing the variance. The joker here, and it is a terrifying one, is that the City Planning Commission was unable to judge a case like Penn Station’s on the proper and genuine considerations involved. … It’s time we stopped talking about our affluent society. We are an impoverished society. It is a poor society indeed that can’t pay for these amenities; that has no money for anything except expressways to rush people out of our dull and deteriorating cities….What this amounts to is carte blanche for demolition of landmarks. The commission’s hands are tied in any interpretation of the public good that rests on the evaluation of old vs. new, or good vs. bad. If a giant pizza stand were proposed in an area zoned for such usage…the pizza stand would be “in the public interest, even if the Parthenon itself stood on the chosen site.Not that Penn Station is the Parthenon, but it just might as well be as we can never again afford a nine acre structure of superbly detailed solid travertine, any more than we could build one of solid gold. It is a monument to the lost art of magnificent construction, other values aside.”

“But once the plans were announced, public reaction was quick and loud….Now alerted, New York’s architects, artists, and writers were outraged at the prospected demise of such a significant structure. Art and architecture institutions almost uniformly called for Penn Station to be preserved….Many were angered that Penn Station was being taken down to make way for commercial development. “New Yorkers will lose one of their finest buildings, one of the few remaining from the ‘golden age’ at the turn of the century”, …The Fine Arts Federation of New York, a non-profit alliance of art and architecture groups established in 1895, also protested the plans for demolition, preferring instead “that a study should be made ‘with a view to preserving those qualities of spaciousness and monumentality for which the station is justly famous.’” – Plosky pp..35,36, 58,59.

Five architects banded together to form the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY) and were joined by writers, artists, historians and the like in the battle to save Penn Station.

“AGBANY, as it had hoped, captured the media spotlight. Its members gave interviews to newspaper, magazine, and television reporters, and succeeded in portraying themselves as determined and civic-minded. Perhaps more importantly, they drew the attention of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, who were finally induced to take a long, hard look at the station slated for demolition.” – Plosky p. 44

Penn Station represents the aspiration of doing something monumental and noble, of private enterprise creating something extraordinary for the benefit of the public. It was an investment that generations that followed would benefit from. The challenge is how you balance the need to preserve what’s best, what’s most important, and the need to continually invent, and change, and grow — because that’s what living places have to do.” Paul Goldberger, Architecture Critic – PBS Documentary – The Rise and Fall of Penn Station.

Huxtable continued her literary assault through the summer of 1963 and completed it with her: “Farewell to Penn Station,” New York Times editorial, October 30, 1963.

“Until the first blow fell no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance. …It’s not easy to knock down nine acres of travertine and granite, 84 Doric columns, a vaulted concourse of extravagant, weighty grandeur, classical splendor modeled after royal Roman baths, rich detail in solid stone, architectural quality in precious materials that set the stamp of excellence on a city. But it can be done. It can be done if the motivation is great enough, and it has been demonstrated that the profit motivation in this instance was great enough. …Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tin-horn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.”

Current Structure (1968–present) See also: Madison Square Garden, Penn Plaza

Long Island Rail Road Concourse, Amtrak Concourse

The current Penn Station is situated completely underground and is located underneath Madison Square Garden, 33rd Street, and Two Penn Plaza. The station spans three levels underground with the concourses located on the upper two levels with the train platforms located on the lowest level. The two levels of concourses, while original to the 1910 station, were extensively renovated during the construction of Madison Square Garden, and expanded in subsequent decades. Despite the improvements, Penn Station continues to be criticized as a low-ceiling-ed “catacomb” lacking charm, especially when compared to New York’s much larger and ornate Grand Central Terminal. The New York Times in a November 2007 editorial supporting development of an enlarged railroad terminal, said that “Amtrak’s beleaguered customers…now scurry through underground rooms bereft of light or character.” Times transit reporter Michael M. Grynbaum later called Penn Station “the ugly stepchild of the city’s two great rail terminals.”

Reincarnation – Redevelopment Plans

Proposed designs throughout the development process, from 1999 (left), 2005 (middle), and 2007 (right)

Resurgence of train ridership in the 21st century has pushed the current Pennsylvania Station structure to capacity, leading to several proposals to renovate or rebuild the station. “This is the first step in finding a new home for Madison Square Garden and building a new Penn Station that is as great as New York and suitable for the 21st century,” said City Council speaker Christine Quinn. “This is an opportunity to re-imagine and redevelop Penn Station as a world-class transportation destination.”

And of course Ada Louise Huxtable weighed in with her November 28, 1994 article in the NY Times: On the Right Track.

“Thirty-one years ago, the shattered marble, travertine and granite columns, caryatids, gods and eagles of Penn Station — modeled after the monuments of ancient Rome by McKim, Mead and White and built for eternity in 1910 — were carted off to the Secaucus meadows, giving New Jersey undisputed title to the world’s most elegant dump. Of the eagles that crowned the station’s walls, a few tokens were reinstalled in front of the new Madison Square Garden, making the contrast between classical and cheesy terminally (pun intended) clear. Because what goes around comes around, usually so that you want to laugh or cry, there are plans for a new Penn Station. The proposal is part of a program in which all of the facilities for Amtrak, New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Railroad will be coordinated for what is now fashionably called intermodal transportation but looks more like a railroad revival and great train station renaissance.”

James Farley Post Office – Moynihan Station

The James Farley Post Office Building

In the early 1990s, U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan began to champion a plan to rebuild the historic Penn Station, in which he had shined shoes during the Great Depression He proposed building it in the James Farley Post Office building, which occupies the block across Eighth Avenue from the current Penn Station and was designed by the same McKim Mead & White architectural firm as the original station. After Moynihan’s death in 2003, New York Governor George Pataki and Senator Charles Schumer proposed naming the facility “Moynihan Station” in his honor. The 1912 post office was itself built over the tracks, allowing direct access to mail trains at special sidings beneath the building.

$83.4 million of federal stimulus money was secured in February 2010, and the shovel-ready elements of the plan were broken off into “Phase 1,” which, together with money from other sources, was fully funded at $267 million. This includes two new entrances to the existing Penn Stations platforms through the Farley Building on Eighth Avenue. Groundbreaking of Phase 1 was on October 18, 2010 and completion is expected in 2016. Phase 2 will consist of the new train hall in the fully renovated Farley Building. It is expected to cost up to $1.5 billion, the source of which has not yet been identified.

Wikipedia link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Station_%28New_York_City%29

Link to Ada Louise Huxtable’s article, How to Kill a City from the May 5, 1963 NY Times: How to Kill a City

Eric Plosky’s Thesis link: The Fall and Rise of Pennsylvania Station

PBS Documentary The Rise and Fall of Penn Station link: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/penn/player/

Pingback: Chautauqua’s Amphitheater Redux v. 3.0 | Drift of the Day